Reviewed by Brunilda Nazario, MD on July 31, 2019

July 31, 2019 — Rebecca Hill thought she was having a heart attack. The 59-year-old Tennessee native, now living in Wasilla, AK, went straight to the ER.

“They did some tests and found out that I had reflux,” she says. “I’ve gone through very many PPIs to try to keep mine under control.”

She was 34. Since then, Hill has used most of the prescription PPIs available and several over-the-counter versions. She hasn’t had any side effects.

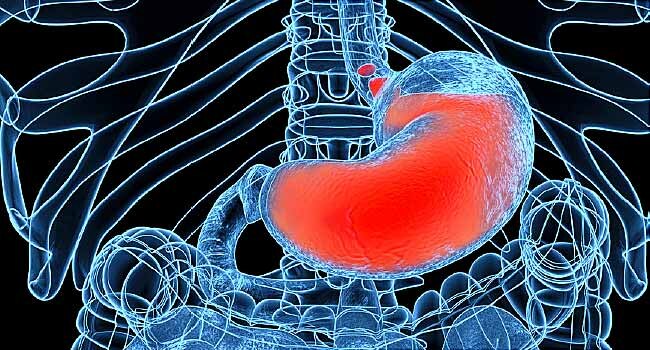

But not everyone has such positive experiences. PPIs, or proton pump inhibitors, are among the most common prescription drugs and are used to treat acid reflux, heartburn, indigestion, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and stomach ulcers. They include omeprazole, lansoprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole, PPIs work by cutting the amount of acid the stomach makes.

There are numerous case studies of the popular prescription drugs causing myriad health problems. But research results are mixed. Some studies have warned of doctors being too quick to prescribe PPIs and patients staying on them for too long. Others have found little reason for concern.

LeighAnn Miller of Knoxville, TN, was on PPIs for years without any problems.

I had initially taken Prilosec probably about 10 years ago,” she says. “It was prescribed by my primary care physician. I Just had some random heartburn and he prescribed it to me, I took it, didn’t have any issues.”

The symptoms got better 3 years later, so she stopped taking it. But the symptoms came back last July, and she was prescribed a different PPI. This time, her experience was much different.

“I began to have what appeared to be bug bites on my forearm,” says Miller, 35. “And at first, it was just a few, then it began to multiply. … I was covered in a rash from head to toe with the exception of my face for 6 months. It did not resolve completely until March.”

She stopped taking the medication as soon as the symptoms began. After several visits to dermatologists and a rheumatologist, after extensive bloodwork and a battery of tests including a biopsy, everything came back normal. Miller says she and her rheumatologist did some research and found that it could be drug-induced lupus.

According to the Lupus Foundation of America, there is a possible but not definitive link between the condition and PPIs in some people.

The experience has soured Miller on PPIs. “I’m not saying that there are not benefits to these medications, but I do think that there is more risk involved than there is benefit.”

A Very Common Drug

Just how risky it is to take these popular drugs has become a source of debate.

While the benefits to patients are undeniable, the drugs’ safety has come into sharp focus, with studies and researchers both defending and questioning the drugs’ benefits, dangers, and widespread use.

In the last few years, thousands of lawsuits have been filed, with patients claiming side effects including kidney disease and bone fractures. According to Drug Watch, a consumer advocacy group, one of the first cases is set for trial in September 2020.

A study published in May in The BMJ, a British medical journal, looked at death rates associated with PPIs.

According to lead investigator Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the study focused on 157,000 veterans who were prescribed PPIs for the first time, following them for 10 years.

“There is a very significant body of evidence that suggests that these drugs (PPIs), when used for a long period of time, especially when they are not medically indicated, are associated with serious side effects and also associated with increased dying from specific causes — namely dying from heart disease, kidney disease, and stomach cancer.”

“There may be other risks as well,” Al-Aly continued, “But, it is important to mention in this context that PPIs are not all evil drugs. They’re also beneficial drugs when used appropriately in the right patient and for the indicated duration of time. In the right patients, these drugs actually also save lives.”

Paul Moayyedi, MD, a professor of gastroenterology at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, says his new research on PPIs, published in early June in the American Gastroenterology Association’s journal Gastroenterology, found no need for worry.

His study was a large trial of 17,598 people whom researchers followed for 3 years. They found no evidence to support claims that PPIs cause serious diseases like chronic kidney disease, pneumonia, diabetes, and dementia.

One group was put on a PPI, and the other was given a placebo. Moayyedi says they found similar rates “of everything” between the two groups, “The rates of heart disease, stroke, pneumonia, fracture, chronic renal disease, and dementia were very similar between the two groups. Cancer rates were also similar, and all cause mortality was almost identical between the two groups.”

Moayyedi says most of the studies of PPIs are observational and therefore less reliable. They only look to understand causes and effects of these medications. But studies like his test the impact of the drugs on patients against those simply given a placebo.

“In other words, they look at people who are on PPI and people who are not on PPI … and see what happens to them over time,” he says. “These have shown increases in risk of diseases such as pneumonia, fractures. However, on average, patients in these databases who are on PPI are sicker than those who are not, and sicker people get other illnesses.”

His message to patients: “There is no harm that we can see so far.”

Folasade May, MD, director of quality improvement in gastroenterology at UCLA Health, is working on a study of the overuse of PPIs. She feels more research is needed. It’s the only way, she says, to test whether a specific medication leads to a specific outcome.

“The reason why these questions and these studies are important is that there are millions of people on PPIs,” she says. “When a medication is this common, even rare adverse effects can impact a lot of individuals. And that’s why it’s important for scientists — those in the laboratory and those that conduct human studies — to expand our knowledge on if and how PPIs are affecting our bodies in ways that we don’t want them to.”

The Consumer Healthcare Products Association represents leading manufacturers and marketers of over-the-counter medicines. In a statement to WebMD, it stands by the safety of these drugs based on years of data and use.

“More than 60 authors from 29 countries recently published results from a large randomized clinical trial confirming the safety of PPIs. Addressing a number of less rigorous studies which have raised concerns that PPIs may be associated with various health risks, the Authors concluded, ‘It is reassuring that there was no evidence for harm for most of these events other than an excess of enteric [intestinal] infections.’ ” According to the American Gastroenterological Association, which published the study in its official journal, this “new research puts safety concerns to rest.”

For 20 years, John Pandolfino, MD, has been prescribing PPIs to his patients. The division chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at Northwestern University told WebMD he’s never had a patient complain about side effects.

“In the grand scheme of things, I do think PPIs are safe, but there are studies that suggest an association between PPIs and some adverse outcomes. However, I think we have to be careful when we look at those particular studies so as to not over exaggerate the cause-and-effect potential, but also to not completely discount them.

“We know that patients that take PPIs are inherently sicker than those who do not take PPIs, and this confounder may bias studies and explain many of these associations.”

Pandolfino thinks doctors who prescribe these medicines must be more vigilant in their follow-up.

“I think this is an important conversation to be having because right now, we’re seeing new studies every week about PPIs. And since they are very similar studies, we see the same results and the same potential bias in the outcomes. This is a wake-up call for all of us to do a better job of educating patients about the risks and benefits of medicines, because all medicines have risks.”

Risks that patients are trying to process as they make decisions about whether to remain on these drugs — or not.