By Dr. Sudip Bose, MD, FACEP, FAAEM

“I have no idea what I’m doing — I’m just a TV doctor … ”

Surely by now many have seen the advertisement using “TV doctors” from the shows, “Grey’s Anatomy,” “Scrubs” and of course “M*A*S*H*” to encourage everyone to have their annual physicals: TV Docs of America.

However, the president of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), Dr. Rebecca Parker, thinks that ad campaign was a waste of money. “The $9 million CIGNA spent on an ad starring well-loved actors playing physicians would have been better spent on patients,” she said. “Emergency physicians fight hard for their patients who are bearing an increasingly large share of the burden for their medical care,” she added. And therein lies the issue — increasingly patients find themselves caught between their health plans and their physicians. Emergency department (ED) physicians countered with their own video of real ED physicians as a parody of the CIGNA ad that included yours truly: ER Doctors of America – Parody of Cigna Health Insurance Ad (that’s me in the light-blue scrubs).

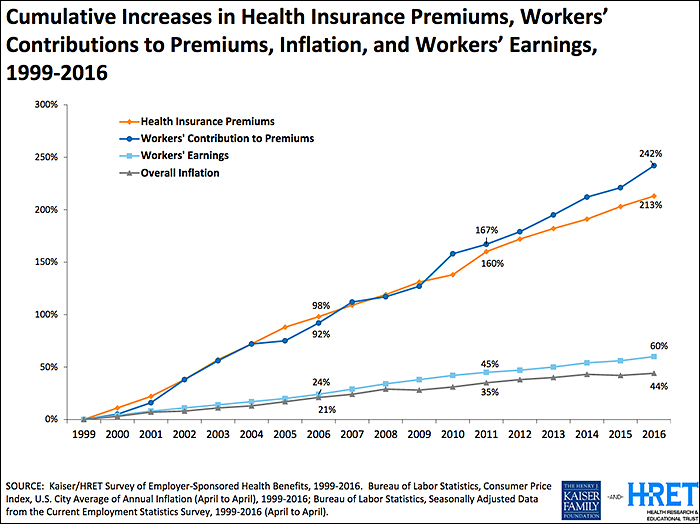

Twenty-plus years ago (when many of those TV doctors were in grammar school) the traditional employer-sponsored health plan was an “80/20” PPO plan (Preferred Provider Organization) where the health plan reimbursed 80 percent of the allowed physician charge and the patient reimbursed 20 percent (co-insurance) after his/her deductible. Unlike today, deductibles back then were perhaps as high as several hundred dollars but rarely in the thousands. Today the average individual deductible exceeds $1,400 according the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and rose double digits just last year (see chart below). The patient has become the largest non-governmental payor in healthcare. Today what the average patient spends on deductibles (which is what a patient pays before their health insurance coverage kicks in), co-insurance and co-pays (patient cost sharing) is less than the average deductible, so the average patient is “underwater” even before insurance kicks in.

While the ACA (the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare) did not create “high deductible health plans” (HDHPs), it certainly accelerated their growth and use among the millions who purchased the benchmark ACA Silver Plans. At above 250 percent of federal poverty level (FPL), folks who purchased Silver Plans have limited first-dollar coverage for preventative care and immunizations but faced HDHP features that many who obtained employer-sponsored coverage have experienced for many years. The net result of these trends and legislation meant that the patient became the largest non-governmental payor in healthcare — and many have experienced the “surprise coverage gaps” that were unheard of 20-plus years ago.

Emergency department (ED) access and treatment are mandated but reimbursement is not:

In 1986, Congress passed the “Emergency Medical Treatment Active Labor Act” or EMTALA, and as a result, the greatest unfunded mandate in healthcare in American history was launched. EMTALA mandated that every person who presented him or herself to an emergency department was entitled to a “medical screening exam” (MSE) and stabilizing care for an emergency. Hospitals are required to have specialty physicians “on call” – e.g. orthopedics, neurology, cardiology, surgery, etc. – so the MSE and stabilizing care could be completed. So health plans knew then and today that their members will not be turned away from the ED regardless of their insurance, deductibles or cost-sharing levels.

In 1997, Congress also enacted the “prudent lay person” amendments to the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA ’97) which required Medicare and Medicaid managed care plans to permit a person’s access to the ED if he/she believed, as “a prudent lay person”, that he/she was having an emergency including suffering from severe pain. BBA ’97 was essential, as prior to that law health plans were requiring that patients call and receive “prior authorization” for ED visits or the plan would retrospectively deny the ED visit for reimbursement. So while access (EMTALA) and treatment (BBA ’97) were guaranteed by federal law more than 20 years ago— unfortunately reimbursement for those mandated services was not itself mandated.

HDHPs and “the myth” of coverage—surprise coverage gaps are born:

Surprise coverage gaps occur when an ED patient reasonably believes that they are having an emergency, are treated by the ED and then discover after the fact that their health plan does not provide fair coverage for the services that were provided to them or their family member. One common coverage gap is that the patient’s health plan will reimburse the physician at or about Medicare levels—leaving a large “balance”, or difference, between that “allowable charge or rate” and the clinician’s charges or the “balance bill”, particularly where the clinicians were “out of network” (OON), which of course the patient has no control over.

The Medicare fee schedule is a creature of federal law and regulations and restricted by those laws in providing for fair coverage for services. In fact, comparing Medicare payments to inflation from 1992 to 2016, Medicare reimbursements have decreased over 50 percent. A non-profit Rand Study in 2016 found that nearly one-third of New Jersey hospitals would have net operating losses if reimbursement rates were at or near Medicare levels. So at a time when non-profit health plan executives are reaping millions in compensation—the top 10 executives at Health Care Service Corp. (owner of BCBS plans in Illinois, Montana, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas) split approximately $58 million in 2015 (see: Modern Healthcare Sept. 26, 2016) —they put profits above patients and stuck the patients in the middle of potential disputes with their physicians.

Hospital-based physicians lead the charge to remove the patients from reimbursement disputes:

National physician specialty organizations such as ACEP, the Anesthesia Society of America (ASA) and a healthcare trade organization, the Emergency Department Practice Management Association (EDPMA) recognized the need to do several things:

- Establish a minimum benefit standard (MBS) that represents fair coverage for OON services and is transparent to the stakeholders

- Remove the patient from the controversy between the physicians and health plans

- Permit mediation of disputes between the plans and physicians that would efficiently address these issues

In 2015, ACEP and EDPMA formed a Joint Task Force (JTF) to develop strategies, white papers and documents to assist their members in addressing their state-level legislative issues. Based on the JTF’s 2016 Strategies White Paper, ACEP and ASA then wrote common principles and proposed solutions (some of which can be found here: ACEP Outlines Top Priorities for Replacing ACA), and now nearly 10 national medical societies have adopted their common sense solutions. An AMA resolution was pending for their June 2017 meeting.

A new non-profit, multi-specialty advocacy organization was born in 2016, Physicians for Fair Coverage, Ltd. (PFC). “The PFC immediately went to work to build on the ACEP/EDPMA JTF work and to write “model legislation” as the OON legislation issues were cropping up in nearly 15-20 states,” said Ed Gaines, an attorney with Zotec Partners, LLC, a large physician revenue cycle management company. Gaines also is chair of the ACEP/EDPMA JTF and serves as model legislation chair for PFC. “ACEP’s survey from February 2017 showed that 95 percent of patients want health plans to cover ED care, so we need to find a fair coverage, patient-centric and transparent solution to these issues,” Gaines said.

As a working ED physician, we see every day that there is a “cost/quality” equation playing out in our hospital EDs — and increasingly the unfunded mandates of well-intended laws from over 30 years ago are bringing the healthcare safety net to the breaking point. “Frequently ED physicians ask me why the health plans seem to be targeting them when the ED is approximately only two percent of the US healthcare expenditures — and I shrug and tell them, ‘because they can and they know their members will be treated by you regardless of their insurance,’ ” Gaines said. “It’s patently unfair for the plans to do this but the ‘House of Medicine’ is together now like never before and we will successfully advocate for fair coverage for the nation’s patients,” he said.

What’s happening is that patients don’t realize just how much healthcare costs are being shifted to them because they generally focus on premiums and either don’t recognize or sometimes even actively ignore these copays and deductibles thinking they’ll be healthy all year and won’t have to worry about those costs.

It’s not just Emergency Departments that are struggling with out of balance costs – it’s the patients across the entire spectrum of health care who are now struggling to shoulder the burden of the costs. Patients readily recognize premiums – the amount they have to pay each month for their healthcare coverage – and largely, they haven’t really felt a pinch there because premiums have risen slowly over the past 10 years. What people often don’t pay that close attention to, however, are the other two legs of costs associated with healthcare – copays and deductibles[DSB1] . A copay is the percentage a patient pays each time he or she sees a doctor. The deductible is how much a patient has to pay before the insurance kicks in. What’s happening is that patients don’t realize just how much healthcare costs are being shifted to them because they generally focus on premiums and either don’t recognize or sometimes even actively ignore these copays and deductibles thinking they’ll be healthy all year and won’t have to worry about those costs.

How patients are becoming self-insured

What we’re seeing now is that an average patient’s healthcare spend is less than the average deductible. The patient is becoming the largest payor in health care because they’re paying for everything and not reaching their maximum deductible. So patients need to pay attention to all costs – premiums, copays and deductibles, and not just premiums alone. Basically patients have become self-insured except in cases of major hospitalization. That’s something that most don’t realize. Companies sell high-deductible plans and people don’t realize they don’t really have coverage – they’ve got a relatively major up-front cost to pay before their insurance kicks in.

Says Dr. Parker, president of ACEP, “Many people don’t realize how little coverage they have until they need medical care — and then they are shocked at how little their insurance pays. Others are not seeking emergency care when they need it — and getting sicker — out of fear their visits won’t be covered.”

As Forbes noted in a 2015 article regarding the ACA: “Furthermore, the strong regulatory and political focus on keeping premiums from increasing ‘too much’ forced insurers to increase deductibles, to the point that most people with ACA plans will not be able to collect benefits, even after paying all the premiums.”

In other words, most people with ACA plans are in the same boat, having such a high deductibles that they are essentially self-insured, because they’ll be spending all their own money for healthcare coverage and will not see any money come their way in terms of compensation or reimbursement from their insurance plan.

A Business Insider story from September 2016 (Americans’ out-of-pocket healthcare costs are skyrocketing) reported on findings of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonpartisan think tank addressing health policy issues, when it released its 2016 annual Employer Health Benefits Survey. They examined the cost of insurance for Americans and found, as the publication Business Insider characterized it, both good and bad news. The good news was that “premium costs, the basic monthly payment to be covered, are growing at an incredibly slow rate compared with recent history. According to the Kaiser survey, average family premium costs increased just three percent between 2015 and 2016, to $18,412. This year’s low family premium increase is similar to last year’s (four percent) and reflects a significant slowdown over the past 15 years. … Since 2011, average family premiums have increased 20 percent, more slowly than the previous five years (31 percent increase from 2006 and 2011) and more slowly than the five years before that (63 percent from 2001 to 2006).”

But, Business Insider also noted in Kaiser’s findings that, “the main driver of the slowing in premiums, unfortunately, is the rise of high-deductible plans. … In 2016, 83 percent of workers have a deductible — an amount that they have to pay themselves for medical care before insurance covers it — with an average of $1,478. The average deductible for workers has gone up $486, or 49 percent, since 2011. Additionally, the survey found that 51 percent of workers have a deductible over $1,000 — the first time this has happened since the survey began in 1999.”

By comparison, workers’ wages increased 1.9 percent between April 2014 and April 2015, according to federal data analyzed by the report’s authors. Consumer prices declined 0.2 percent.

‘We’re seeing premiums rising at historically slow rates, which helps workers and employers alike, but it’s made possible in part by the more rapid rise in the deductibles workers must pay,” Drew Altman, CEO of Kaiser was quoted as saying.

A story in the Los Angeles Times quantified the point made by Altman and the Kaiser Foundation findings. “Over the past decade, the average deductible that workers must pay for medical care before their insurance kicks in has more than tripled from $303 in 2006 to $1,077 today [and up to $1478 in 2016 as seen in the chart above], according to the report from the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research & Educational Trust,” reporter Noam A. Levy wrote in 2015. “That is seven times faster than wages have risen in the same period.”

What that means is that for the first time in our nation’s history, patients have become the primary payor for their medical costs.

“It’s a quiet revolution,” Altman was quoted as saying in the LA Times story. “When deductibles are rising seven times faster than wages … it means that people can’t pay their rent. … They can’t buy their gas. They can’t eat.”

Unfortunately that’s not an exaggeration.

How did we get here?

The cost of healthcare has been growing rapidly for decades. History shows that our modern healthcare system really saw its genesis back in 1929 and 1930 with the emergence of what eventually would became a well-known health insurance company, especially in the 1950s and 60s – Blue Cross-BlueShield. In 1929, Blue Cross started out as a partnership between Baylor University hospital and financially struggling patients. It was the year of the start of the Great Depression with the crash of Wall Street and families trying to figure out how to get through it all. Blue Cross began as a plan to allow patients to pre-pay 50 cents a month, which would allow a person 21 days of hospitalization a year. The plan proved so popular that it grew quickly – from about 1,300 in its early years to about three million in 10 years.

In 1930, a group of physicians quickly adopted the Blue Cross idea when they saw the kind of success it was having and created Blue Shield, which developed a plan similar to the hospitalization plan of Blue Cross; but this partnership was between physicians and patients. Again, for a monthly fee, Blue Shield members gained access to physician services. This plan also proved extraordinarily popular.

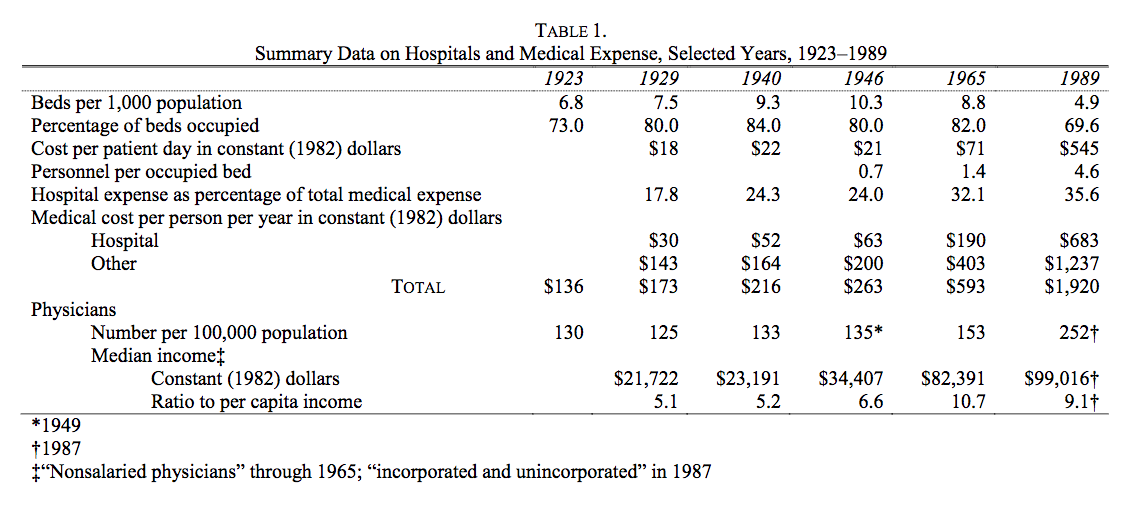

According to an often-cited and well-known study in healthcare circles by Milton Friedman published in 1992, “The cost of hospital care per resident of the United States, adjusted for inflation, rose from 1929 to 1940 at the rate of 5 percent per year; the number of occupied beds, at 2.4 percent a year (see Table 1 below). Cost per patient day, adjusted for inflation, rose only modestly.”

Moreover, according to Friedman’s research, The situation became very different after the end of World War II: “From 1946 to 1989 the number of beds per one thousand population fell by more than half; the occupancy rate, by an eighth. … [but] cost per patient day, adjusted for inflation, [rose] an astounding twenty-six-fold, from $21 in 1946 to $545 in 1989 at the 1982 price level. One major engine of these changes was the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.” (My bold face highlight.)

The chart above accompanying Friedman’s research is particularly illuminating. A few highlights from Friedman’s study:

- “Cost per patient day, which had already more than tripled from 1946 to 1965, multiplied a further eightfold after 1965.”

- “Growing costs, in turn, led to more regulation of hospitals, further increasing administrative expense.”

- “Anecdotal evidence suggests that increased administrative complexity played a major role in the explosion of total cost per patient day and led to a shift from hospital to outpatient care …”

And note in the chart above how much the total medical cost per person per year (in 1982 dollars) jumped from 1965, when Medicare was enacted, to 1989 – from $593 per person to $1,920.

In a publication put out by Deloitte Center for Health Solutions (“Dig deep: Impacts and implications of rising out-of-pocket health care costs,”) they write:

“Even though more consumers are gaining health insurance coverage (from the mid-60s through the late 80s to modern day with the expansion of Medicare under Obamacare), they are by no means insulated from the burden of health care costs. Consumers are paying more of their health plan premium and experiencing higher out-of-pocket (OOP) cost-sharing for all types of health care services. These increases are expected to continue as employers shift to high-deductible offerings and individuals gain coverage through insurance marketplaces (also known as public health insurance exchanges).”

As physicians, we want fair insurance coverage for all patients to bring costs under control and have manageable coverage. Right now, not only are the costs not manageable, they’re often not even known by the patient.

Let’s say a patient comes through the ED and their costs are covered there, but then perhaps they get admitted to a surgical service and that assistant surgeon is out of network (OON), or a plastic surgeon comes in and sews up a laceration, and that plastic surgeon is not in network; the patient will get a “balance bill.” A balance bill is the difference between what the OON providers charge (let’s say that’s $1,000) and the amount reimbursed by the insurance carrier for that OON charge (let’s say that’s $450). So the patient’s left with having to pay $550, or the balance of the bill. The patients are then getting stuck with that bill, and that’s a problem.

It reminds me of an analogy I made in a previous write up (Obamacare: Three Keys for Improvement) where I compared insurance coverage to dining in a restaurant. I wrote:

“Have you ever been to a restaurant, paid what you thought was your bill, left, and then weeks later gotten a half-dozen or so bills in the mail related to your service at that restaurant? No? You say you haven’t? Perhaps you got a bill from the sous chef, who was an independent contractor not working directly for the restaurant? Maybe one from the food expediter, and then the one from the pastry chef, the maitre’d who escorted you to your table, the busboy who cleaned and set the table before you sat down and then cleared dishes after each course and filled water glasses? No? And just think — some of those people were in your preferred network of restaurant service providers (and you got a good deal on the cost of their services), but some weren’t (and you were charged what looks like an exorbitant amount).”

I’ll say it again: as physicians, we simply want fair insurance coverage for all patients. Insurance companies must provide fair coverage for their beneficiaries and be transparent about how they calculate payments. They need to pay reasonable charges, rather than setting arbitrary rates that don’t even cover the costs of care. Insurance companies are exploiting federal law [EMTALA] to reduce coverage for emergency care, knowing emergency departments have a federal mandate to care for all patients, regardless of their ability to pay.

As the president of ACEP, Dr. Parker, puts it: “Patients should not be punished financially for having emergencies or discouraged from seeking medical attention when they are sick or injured. No plan is affordable if it abandons you when you need it most.”

We all should be able to agree with that. And we all need to work together to get there. As I’ve written before, change has to focus on the center of the epicenter of healthcare — the doctor-patient relationship.

To learn more about Dr. Sudip Bose, MD, please go to SudipBose.com and visit his nonprofit TheBattleContinues.org where 100% of donations go directly to injured veterans.