The novelty of the COVID-19 vaccines may seem daunting for some, and it is natural for questions to arise on their effectiveness. In this feature, we examine the difference between effectiveness and efficacy, compare the COVID-19 frontrunner vaccines to other vaccines, such as the flu shot, and compare their safety considerations.

As Pfizer/BioNTech roll out their COVID-19 vaccine throughout the United Kingdom and the United States, the world wonders how effective it will be.

Looking at the three leading vaccines that we have previously reported on, Pfizer/BioNTech boasts 95% efficacy, the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine candidate has an average of 70% efficacy, while the Moderna vaccine candidate reportedly has 94.1% efficacy.

But what does this say about their effectiveness? And how does it compare with vaccines against the flu, polio, and measles?

Effectiveness vs. efficacy — what is the difference?

Firstly, it is worth noting that “effectiveness” and “efficacy” are not the same. Despite news outlets frequently using them interchangeably, efficacy refers to how a vaccine performs under ideal lab conditions, such as those in a clinical trial. In contrast, effectiveness refers to how it performs in the real world.

In other words, in a clinical trial, a 90% efficacy means that there are 90% fewer cases of disease in the group receiving the vaccine compared with the placebo group.

However, the participants chosen for a clinical trial tend to be healthier and younger than those in the general population, and they generally have no underlying conditions. Furthermore, researchers do not normally include certain groups in these studies, such as children or pregnant people.

So, while a vaccine can prevent disease in a trial, we might see this effectiveness drop when administered to the wider population.

However, that is not in itself a bad thing.

Flu shot effectiveness

Vaccines do not need to have high effectiveness to save thousands of lives and prevent millions of disease cases.

The popular flu shot, for example, has an effectiveness of 40–60%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

However, during 2018–2019, it prevented around “4.4 million influenza illnesses, 2.3 million influenza-associated medical visits, 58,000 influenza-associated hospitalizations, and 3,500 influenza-associated deaths.”

It is also worth noting that the flu vaccine’s effectiveness varies from season to season, due to the nature of the flu viruses circulating that year. Determining the precise rate of effectiveness can be challenging.

Finally, it bears mentioning that the number of doses can also improve effectiveness for some vaccines. For the flu shot, two doses of the vaccine instead of one can offer a protection boost, but this benefit is limited to only a few specific groups, such as children or organ transplant recipients.

The booster dose does not seem to benefit people over the age of 65 or those with a compromised immune system.

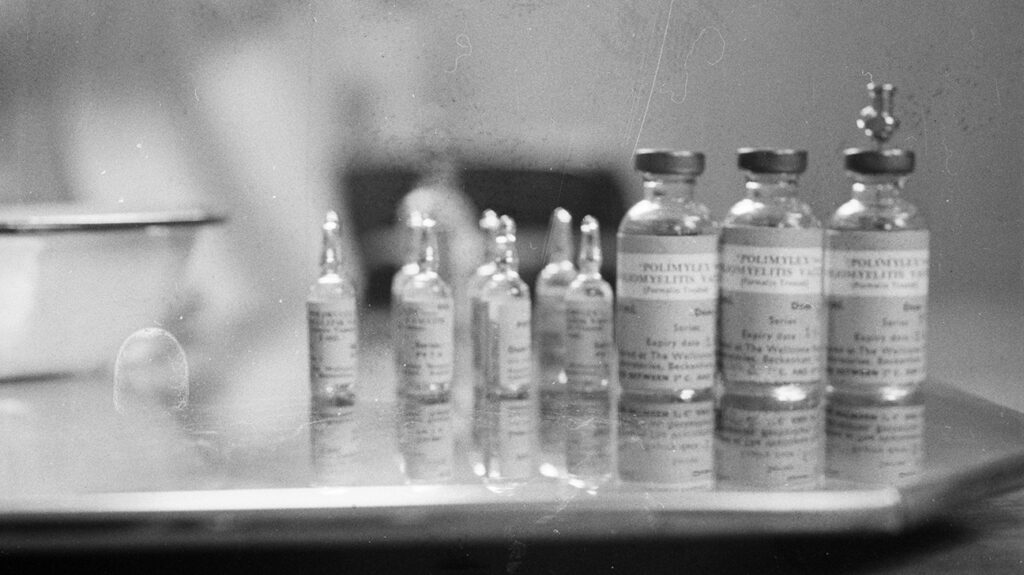

By contrast, as we will see below, for vaccines, such as the ones against polio and measles, a higher number of doses is required to achieve peak effectiveness.