By Dr. Sudip Bose, MD, FACEP, FAAEM

As the 2016 presidential campaign came to a close and we elected a new president, polls showed that of the half-dozen things that most concerned Americans, health care was one of the major topics. No real surprise there.

There are advocates for the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, who say that statistics show that 21 million more Americans got health care who didn’t have it before, and that those least able to afford it were the ones who benefitted from the ACA.

There are advocates against the Affordable Care Act who point to what they say is a broken system, with insurers exiting the marketplace and premiums rising by double and in some cases triple digits — so much so as to render plans in the “Affordable” Care Act unaffordable.

Where do you start with a topic as broad and overwhelming as this? Trying to look at it on balance, there are some things the ACA got right and some it didn’t. Let’s look at a few key issues that I think need to be addressed:

Get Costs Under Control

The future of Obamacare is uncertain with president-elect Donald Trump about to be sworn in. There are a couple of things that we know for certain, however — insurance premiums will spike next year, and things will change under Trump. Trump has pledged to repeal and replace Obamacare, so stay tuned, there are going to be ongoing conversations about this.

A recently released government report says that health care premiums are going up in 2017. They’re going up a lot. In order for the Affordable Care Act or any health insurance to work, you need everyone in the pool, so to speak. But what’s happening is that only the sick patients are joining the pool. So the healthy patients are opting out and not paying premiums – they’re not getting health insurance in many cases. Health insurance companies are losing millions of dollars and they’re pulling out and not providing coverage under the Affordable Care Act. We’re seeing that across the country.

According to a report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), prices across the country could go up by double digits, although not everywhere. Premiums in some states could double while premiums in other states could actually drop. A mid-level benchmark plan could increase an average of about 25 percent. But there’s going to be less choice. One fifth of consumers can only pick plans from one insurer.

Let’s take a worst-case scenario. Let’s talk about the state of Arizona. One of the unsubsidized premiums for a hypothetical single, 27-year-old male and the benchmark second-lowest cost silver plan — that premium would jump significantly. So what does that look like? A $200 monthly premium in 2016 would become close to $400 in 2017. People who get their insurance through work probably won’t see the spikes as much, because they’re not going through Healthcare.gov for their insurance, which is what this article is focusing on. But their prices will be going up as well. It’s happening across the country. And we’re talking right now about the basic plan sticker prices. There are subsidies available if you qualify that will bring the price down, and as people make less, there will be increased subsidies for that. So the key lesson is a simple one: you need to do your homework, look at different health plans, get a good review of the plans and see what’s best for you.

Have you ever been to a restaurant, paid what you thought was your bill, left, and then weeks later gotten a half-dozen or so bills in the mail related to your service at that restaurant? No? You say you haven’t? Perhaps you got a bill from the sous chef, who was an independent contractor not working directly for the restaurant? Maybe one from the food expediter, and then the one from the pastry chef, the maitre’d who escorted you to your table, the busboy who cleaned and set the table before you sat down and then cleared dishes after each course and filled water glasses? No? And just think — some of those people were in your preferred network of restaurant service providers (and you got a good deal on the cost of their services), but some weren’t (and you were charged what looks like an exorbitant amount).

Another issue related to costs is transparency. We must know clearly what treatments will cost. Have you ever been to a restaurant, paid what you thought was your bill, left, and then weeks later gotten a half-dozen or so bills in the mail related to your service at that restaurant? No? You say you haven’t? Perhaps you got a bill from the sous chef, who was an independent contractor not working directly for the restaurant? Maybe one from the food expediter, and then the one from the pastry chef, the maitre’d who escorted you to your table, the busboy who cleaned and set the table before you sat down and then cleared dishes after each course and filled water glasses? No? And just think — some of those workers were in your preferred network of restaurant service providers (and you got a good deal on the cost of their services), but some weren’t (and you were charged what looks like an exorbitant amount). Of course, you had no idea on the night you visited and no control over whether or not any of your preferred restaurant service providers were on duty.

Sounds kind of silly, doesn’t it? I mean, who would go to a restaurant that charged like that? Who would go to a restaurant that blind-sided you with bills weeks after you dined there until your total bill at that restaurant ended up being about 10 times what you thought you would pay? Certainly not I, not you … not anyone, I would suspect.

So why should we put up with an arrangement like that with our health care costs? We need simplified, complete and total transparency into the costs of our care when we enter the hospital for a scheduled procedure, or even for emergency treatment. There should be no hidden costs that a patient gets hit with weeks or months after the fact.

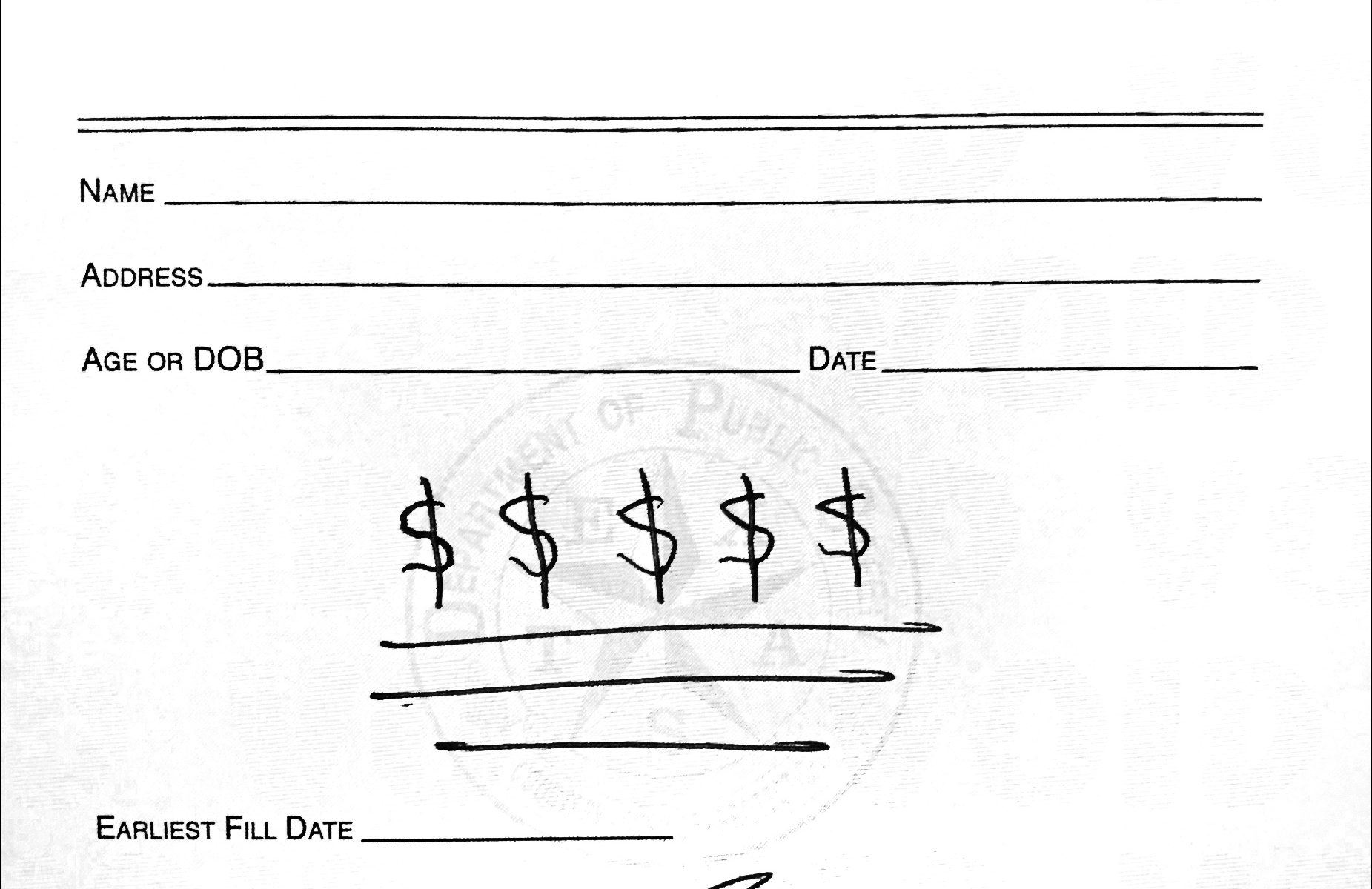

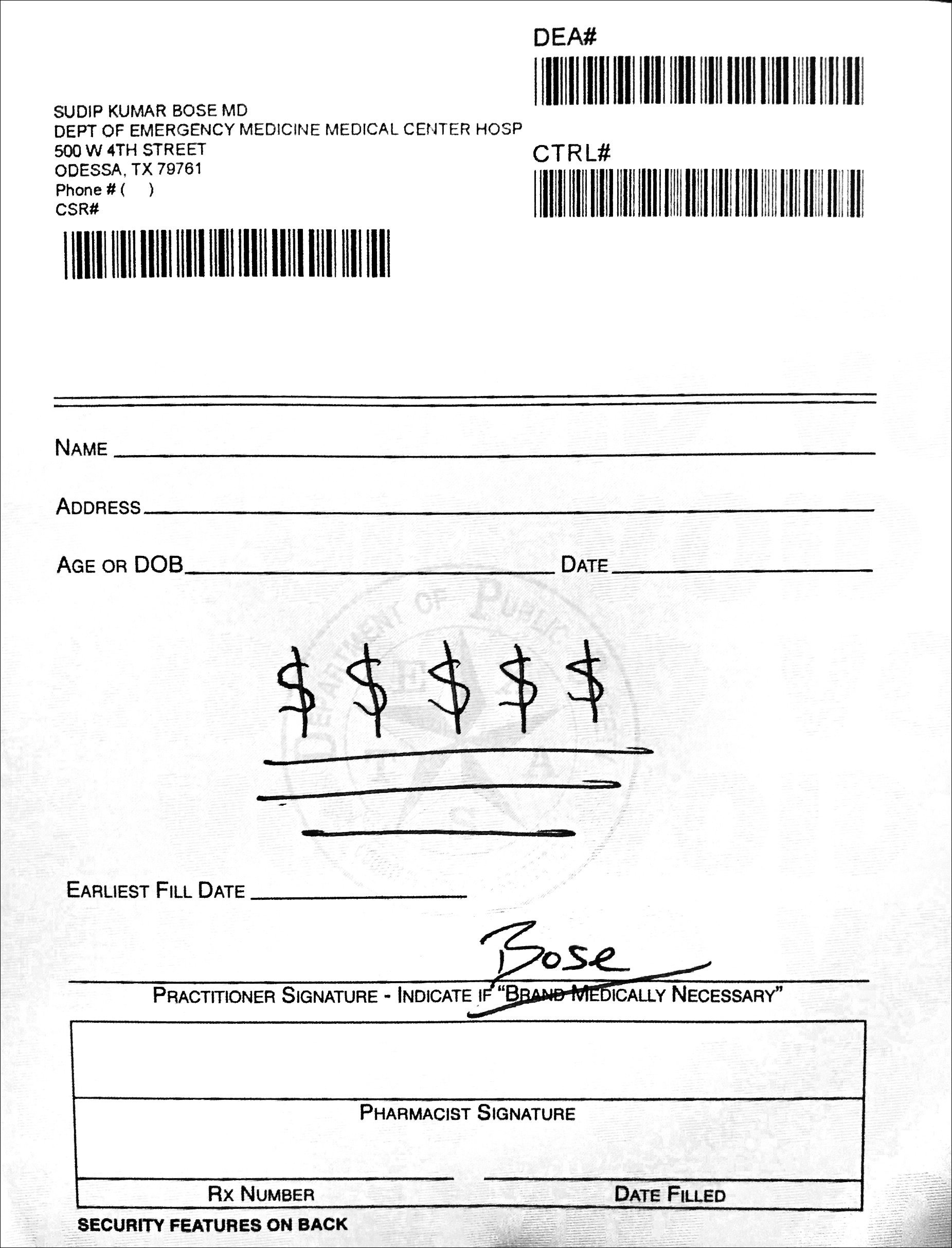

How, then, do we get costs under control? I would propose the kind of plan that Dr. Ben Carson has championed — that we create Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) for people from the day that they are born to the day that they die, at which time they can pass any money in their HSA on. We can pay for these HSAs with the same traditional dollars that we currently pay for health care. Even if the government populates everyone’s Health Savings Account — all 315,000,000 of us in the US at $2,000 a year, that’s $630 billion dollars. That’s not a whole lot compared to what we’re spending now, and everybody would have health care and you could always add more to your plan on your own. What you add on your own should be pretax and never be taxed, thus allowing everyone to save taxes and save for their heath. Your employer could add to it, anybody could add onto it; but everybody would have basic care. And that’s what we’re trying to do. If we bring it into the free market, that makes it work much better. But we also need to incorporate tort reform, and digital, electronic medical records. I would embed those records in a microchip that the patient can keep, rather than have them floating in cyberspace. I think people’s medical records are much too important and much too private to be drifting in cyberspace. Those are some of the major components of the program, and I think that could be done for considerably less money than we’re spending now.

Also, to expand on a point above, we need to give people the ability to shift HSA funds within a family or to anyone of their choice. So if one member of a family or a friend or anyone needs a little more help with coverage during a challenging illness or injury, people can shift some of their funds to that individual. We’re essentially making each family their own insurance company. This can provide families with an enormous amount of flexibility; and when a person dies, they can pass their HSA funds along to a family member or members. It gives you enormous flexibility without a middleman.

Now, it doesn’t take care of catastrophic health care, but you can buy a catastrophic health care policy, and it’ll cost you a lot less because the vast majority of medical issues will be taken care of through your HSA. Because 80% of the medical encounters a patient has are going to be handled through HSAs, you won’t have a big burden on major medical or catastrophic insurance. So the costs of that will plummet, and it will be much easier to acquire. And I would make that something you could acquire from any place in the country or even any place in the world that met our US insurance standards.

By doing this, we’re putting the responsibility for health care in the hands of the patient and the health care provider. What do you need for good health care? You need a patient and you need a provider. Along came a middleman to facilitate the relationship and now the middleman is the primary entity with the patient and the health care provider at its beck and call. That doesn’t make any sense.

Having individual HSAs also can help incentivize people to become more immersive in their overall health care rather than just looking for ways to treat the symptoms of their illnesses. This helps get to the core of and individual’s health care, and that is to help that individual understand, manage and maintain proper health as best they can through proper nutrition and exercise and by “keeping your inner army strong.” Now, to preserve as much of that $2,000 a year HSA money provided by the government and the additional amount people choose to add (funded with pretax dollars so individuals have less taxes and become incentivized to shelter even more funds for health care), individuals may become more aware of the impact of their own health care decisions on their own bottom line. Maybe they’ll consume fewer cheeseburgers or milkshakes within a month and eat more fruits and vegetables; or perhaps smoke less or quit smoking altogether; or engage in a regular walking or workout routine. Who knows where it could lead?

Many people won’t save — after all HSAs aren’t a new concept and a vast number of people don’t have them, even though they’re currently available through some employers. But with baby boomers retiring and younger workers transitioning to self-employment as technology and artificial intelligence take over jobs people were previously performing, the focus should be on decreasing a person’s overall tax burden by being able to spend for health care with pre-tax dollars.

Recognize that in America we spend twice as much per capita on health care as many other countries. And yet we have these horrible access problems. So we have adequate resources, we just don’t use them in an efficient way.

“What I propose we should do to open access up to more individuals is to expand the emergency room model. If you think about it, there’s only really one place where, 24-7, 365 days of the year, you can be seen by a physician — and that’s in the ER. So we need to expand on that model. Let’s multiply what works.”

Improve Access to Health Care

Even if you have an HSA, even if you have catastrophic insurance, if you can’t get access to your doctor, that’s a problem. And right now, it can take weeks to see your primary care doctor for an appointment. Averages vary widely, depending on location, and hover around 14-24 days.

In our current system, even with the advent of Obamacare, it won’t get better; it will get worse. I’m worried, because if you look at it statistically, by 2030, which isn’t that far away, one out of two people — 50 percent of the US population — are going to be obese. One out of three of us, by 2030, are going to have diabetes. In addition to that, there are aging baby boomers, and we’re only at the beginning of that generation’s march to retirement age. That will be ongoing for another 20 years. So there’s a big stress on our system that will continue to grow over the next couple decades.

What I propose we should do to open access up to more individuals is to expand the emergency room model. If you think about it, there’s only really one place where, 24-7, 365 days of the year, you can be seen by a physician — and that’s in the ER. So we need to expand on that model. Let’s multiply what works.

What does the anatomy of that solution look like?

Emergency rooms have become dangerously overcrowded (see my write-up on ER issues: The Emerging State of Medical Care In Our Nation’s Emergency Rooms). It may sound counter-intuitive, but sending more people to the emergency room is my proposed solution. Instead of offering only emergency services, however, the ER would encompass mental health and primary care clinics and in essence create a “central care system,” allowing more people to be seen. Emergency rooms already provide 24-hour care to people who are in need of urgent medical attention, but also for those whose work schedules or other issues make it impossible to be seen during regular clinic hours. In the ER, the infrastructure already exists to see anyone with a common cold to mental health issues to heart attacks and strokes 24 hours a day, 7 days a week; obtain labs, X-rays and CT scans. Within an ER environment, people can get these done same-day; right now, it takes days to more likely weeks to get these scheduled through a Primary Care Physician (PCP). It’s logical to use what already works. It’s also logical to provide significantly more funding to these emergency departments to carry this extra burden. We don’t even need to spend more, we just need to redistribute already allocated health care funds, since currently emergency care represents less than 2 percent of the nation’s health care expenditure.

However, it is a dangerous fantasy to think that urgent care centers or mini-clinics can eliminate ER overcrowding. While urgent care facilities are staffed with competent medical providers and use the best technology for many injuries and illnesses, they lack the expertise and the amount of resources to handle true emergencies. The wrong patient visiting an urgent care center in order to save money or time could well wind up costing a life. Urgent care centers are very much needed and should continue to be available, but they are no substitute for emergency care. We need to increase funding these safety nets within our health care system. I think the problem with ERs, as I’ve mentioned previously, is that they must treat you even if you don’t have any insurance. So there has to be a mechanism by which when people walk in for treatment and they’re uninsured, the facility has to be compensated by the work they do for patients from somewhere — and this is where the government comes in. The government has to fund ERs to some degree.

With today’s 24-hour lifestyle, we can buy groceries, fly across the world, tweet a message to thousands of people, and even work out at the gym at any time, day or night. Medical care has to adapt to the fast-paced world in which we live. When a patient comes into the hospital central care system, he or she will initially present to a main check-in area where staff will determine how urgently the individual needs to be seen. A person experiencing a heart attack will be sent immediately to the emergency department, but a child with bronchitis will be directed to see another qualified practitioner quickly in the adjacent clinic or urgent care. By the same token, patients presenting with problems that do not need urgent treatment will be asked to schedule an appointment with a doctor at a local clinic within a couple of days.

With the central care system, there will be physician assistants and nurse practitioners who are available to treat less urgent issues and thereby reduce waiting times. In this way more people can be seen appropriately, without sacrificing quality or timeliness of care. Think of a place like this as a hub. Patients come into a central location initially to be triaged. For a patient who is having or has had a heart attack — off he goes through the big double doors for immediate care; for someone with a broken leg — off he goes through door No. 7 to the orthopedist for a complete workup; for an elderly woman who is feverish, coughing uncontrollably and has had a history of pneumonia recently — off she goes through door No. 3 for treatment.

Of course patients needing to see providers for less critical situations will still spend some time in the central care waiting room, just as they currently do in doctors’ offices and urgent care clinics. Using that time to educate people will improve understanding about disease prevention, healthy living, vaccinations, home treatments for common illnesses like flu and colds, and other issues related to health – call it “wait to educate”. Introducing basic health education while people wait to see providers in the central care system may help them to avoid or more effectively manage chronic diseases and other common health issues. If we use the wait to educate concept, the information can be spread by word of mouth and it has the potential to benefit the entire community. In addition, there can be a virtual arm to this waiting room using a platform like liveClinic (described below).

Get Third Parties Under Control

The center of the epicenter of health care is the doctor-patient relationship. Any other forces or third-party entities that come in should not be inserted between the doctor and the patient, but should be aligned behind the patient, supporting the patient, and/or behind the doctor, supporting the doctor.

Now, the first two ideas I’ve outlined above are certainly workable, but unless you manage the special interest groups and protect the doctor-patient relationship — the insurers, the lawyers, the lobbyists to name a few — it will chip away at that doctor-patient relationship, which is the core. Third parties pull down the relationship, making it more difficult for the doctor and more difficult for the patient.

With respect to health care, a third-party is typically known as the insurance company that pays the provider on behalf of the insured. In our current system, the consumer pays a co-pay — only a small portion of the actual cost. At first glance, you may be just fine with that arrangement. You probably don’t know and will never know the full retail value of the procedure and what negotiations the health care companies have done behind the scenes. So you don’t really get a true sense of what something costs.

Let’s look at this from the perspective of a health insurer — and we’re not bashing health insurance here, health insurance is a good thing. Insurers have saved countless families from going bankrupt due to health care costs (which is the number one reason for bankruptcy in America). Insurance is NOT about saving money — it’s about protecting people financially and protecting people’s assets when they have a catastrophic loss. People pool their money together by paying premiums every year so that when they have a big loss they don’t get hit so hard financially. Originally insurance was supposed to be for big catastrophic losses but insurance companies adapted and started paying out for smaller claims.

Another thing I’m worried about regarding rising costs of health care is that it’s having a chilling effect on people even trying to see a doctor. I’ll reference a publication put together by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP — of which I’m a member) that shows that patients are delaying their health care. They’re holding off even seeing a doctor because they don’t know how much things are going to cost and they have a high deductible; they’re afraid they’ll get hit with unexpected bills that they won’t be able to afford. (Remember that first section above regarding the restaurant scenario?) And the insurance companies, what they’re trying to enact in the way of cost cutting is really, if you look at the numbers, profit boosting. On the one hand, the ACA contains provisions to protect consumers from being gouged by insurance companies at the worst and from unfair premium increases at the least. The ACA contains two checks — a “Rate Review Provision” that requires insurance companies to justify rate hikes of more than 10% — as well as an 80/20 rule, which defines how insurance companies can use the monies from premiums collected. Insurance companies offering ACA plans are mandated to spend at least 80% of premiums they receive on individual health care and “quality improvement activities” and not on overhead, administrative and marketing costs. If they don’t hit that mark, then they have to return money to the insured in the form of a rebate. This was written into the ACA regulations to ensure that health insurance companies couldn’t raise premiums to boost profits. On the other hand, the largest companies had the funds to merge. They increased their profits by offering less. (After all, you either maintain your profit margin by increasing revenue or cutting costs – sometimes both.) They’re narrowing their network plans, for example, and all of a sudden your doctor is not covered in the network plan, you don’t have enough primary care physicians in your plan, there isn’t a specialist for you out there. You get a head bleed, and a neurosurgeon is not covered. That means more money coming out of an insured individual’s pocket. That’s a problem.

That’s why I started liveClinic (liveClinic.com). Our vision is to “take care of the rest” so doctors can focus on taking care of patients. The platform allows patients to communicate safely and conveniently with a doctor of their choosing. Regulatory codes and quality guidelines often hinder the free flow of information between patients and their doctors. At liveClinic, we aim to break down these barriers without breaking the rules. Designed with doctors in mind and patients at heart, this powerful and intelligent web platform and the corresponding interactive mobile applications saves the physician time and money by giving doctors the freedom to handle routine visits quickly and remotely, via voice or video chat. Having more options not only increases productivity, but encourages self-management among patients and extends clinical reach. This very same technology provides patients with more options for communicating with their doctor, and reduces the amount of time spent in the waiting room, away from work and school.

liveClinic incentivizes doctors by decreasing their time on tedious administrative burdens so they can focus on patients. And I think you have to incentivize the doctor. People always focus on the patient, and that’s OK, but if you incentivize the doctors you get happy doctors. Most doctors go into medicine to help their patients; so they will do that. But right now, under the status quo system, doctors are burning out. It’s not good.

According to a report in US News and World Report from earlier this year:

“Awareness is growing around the stress that doctors-in-training and those practicing medicine experience. The statistics are alarming to some degree. Approximately one-third of physicians report experiencing burnout at any given point. As a matter of fact, doctors are 15 times more likely to burn out than professionals in any other line of work, and 45 percent of primary care physicians report that they would quit if they could afford to do so. Physicians have a 10 to 20 percent higher divorce rate than the general population and, sadly, there are 300 to 400 physician suicide deaths each year.”

Doctors are getting jaded because of all the paperwork, the decreasing reimbursements, constantly growing administrative burdens, and the fact that we can order a pizza, a hotel room, an Uber ride immediately on a smart phone, but our patients can’t even get access to us, so they seek care elsewhere (see my previous write up on the state of emergency rooms). Fantasy football websites have better user interface and functionality than do most electronic health care record databases. (The average ER doctor clicks on a mouse 4,000 times in a 10-hour shift according to a recent study – while still trying to see patients!)

Everything’s getting disjointed; people are going to ERs and urgent care clinics instead, and then their primary doc has no idea what’s going on. So change has to focus on the center of the epicenter — the doctor-patient relationship. That’s what the liveClinic platform does.

There are ways, given the current state of health care in America, that we can make positive, even transformational changes if we allow our thinking to evolve and focus on a different way of setting expectations on the patient side, the doctor side, and the third-party side — all three phases. We must change, we can change, and change will be good for the entire health care industry and our overall economy. As a nation we can excel and lead the world in health care just as we do in other areas. After all, our health is our MOST valuable possession; without it we cannot lead our lives or the world.

To learn more about Dr. Sudip Bose, MD, please go to SudipBose.com and visit his nonprofit TheBattleContinues.org where 100% of donations go directly to injured veterans.